Face the Fear, Worldbuild the Future: The Games and World of Project Moon

Open the curtain, lights on...

Foreword: This was originally written as an entry for Astral Codex Ten/Scott Alexander’s Everything-Except-Book Review Contest 2025, as such it will have been written in a way that won’t indirectly reference past concepts—where applicable I’ll simply restate/self-plagiarize them directly—I’ll also have finished it long before I’ve published it here (finished the submitted draft 3/18/25).

“The City” is Judge Dredd meets Warhammer 40k with plenty of shounen anime sprinkled on top. Its official map, as shown here, implies that it occupies approximately 44000 square kilometers, or around 17000 square miles (roughly 36 times the total area of New York City) and is home to a population in the billions1. It is separated into 26 distinct districts, each named for a letter of the English alphabet spiraling out from the center (though District 26 is conspicuously absent from any maps).

Each district, which is large enough that they’re generally distinct in both in culture and landscape2, has what is collectively referred to as a “Wing”, made up of the district’s quasi-sovereign lettered megacorporation and its “Nest”—relatively normal, walled-garden subdistricts which also serve as the safe zones for the district’s corporate employees. In classic future-cyberpunk-dystopia fashion, each corporation has at least one powerful “Singularity” that gives it access to some aspect of advanced technology which helps to cement their local corporate hegemony. However, the de facto rulers of the City are the “Head”, composed of A, B, and C Corp, which is unfathomably powerful and oversees all aspects of City life. Everywhere else within the City’s borders but outside of a Nest is collectively referred to as the Backstreets—sprawling, dangerous lawless slums that cover most of the City and are generally neglected by the Wings, home to all manner of gangs ranging from low level street thugs to members of the five organized crime Syndicates collectively referred to as the “Five Fingers”.

I’ll return to this comparison, but the City is a fertile stage for the imagination in much the same way many tabletop game settings are. There are many important established facts about the world and pieces of its history—and numerous known and unknown organizations, factions, and individuals of wildly varying flavor and power level—but the door is left wide open to dream of almost any random adventure that follows the basic rules of the world.

Project Moon is an independent South Korean video game development studio founded in 2016. Their three modestly well-known games that share the City setting are:

Lobotomy Corporation, a monster management sim.

Library of Ruina, a TCG-style card battler.

And Limbus Company, a gacha RPG that shares many of Library of Ruina’s mechanical concepts.

There are additional connected webcomics and announced future games that also tell stories that take place in the City, but for now we’re just going to examine these three games and their place in the world. I’m going to do my best not to spoil the plots of the games themselves and instead mostly comment on their mechanics and the ways they interconnect since that’s plenty interesting. That said, if you consider discussion of lore, worldbuilding, and explanations of complex game mechanics to be spoilers, here is your spoiler warning.

None of these games are strictly new—the latest of the three will have recently had its 2nd year anniversary event—but they’re very cult fan-y. I’m writing about these now partly because they happen to be what I’ve been playing recently, partly because these games are just obscure enough in the right way for me to flex my video game hipster cred, and partly because I can use them as a framework to tie together some of my broader, general thoughts on video games.

In the course of this review I’m going to give a brief(?) description of each of the three games, touch on aspects of the background setting, and then go from there on to a broader critique of writing and worldbuilding in games.

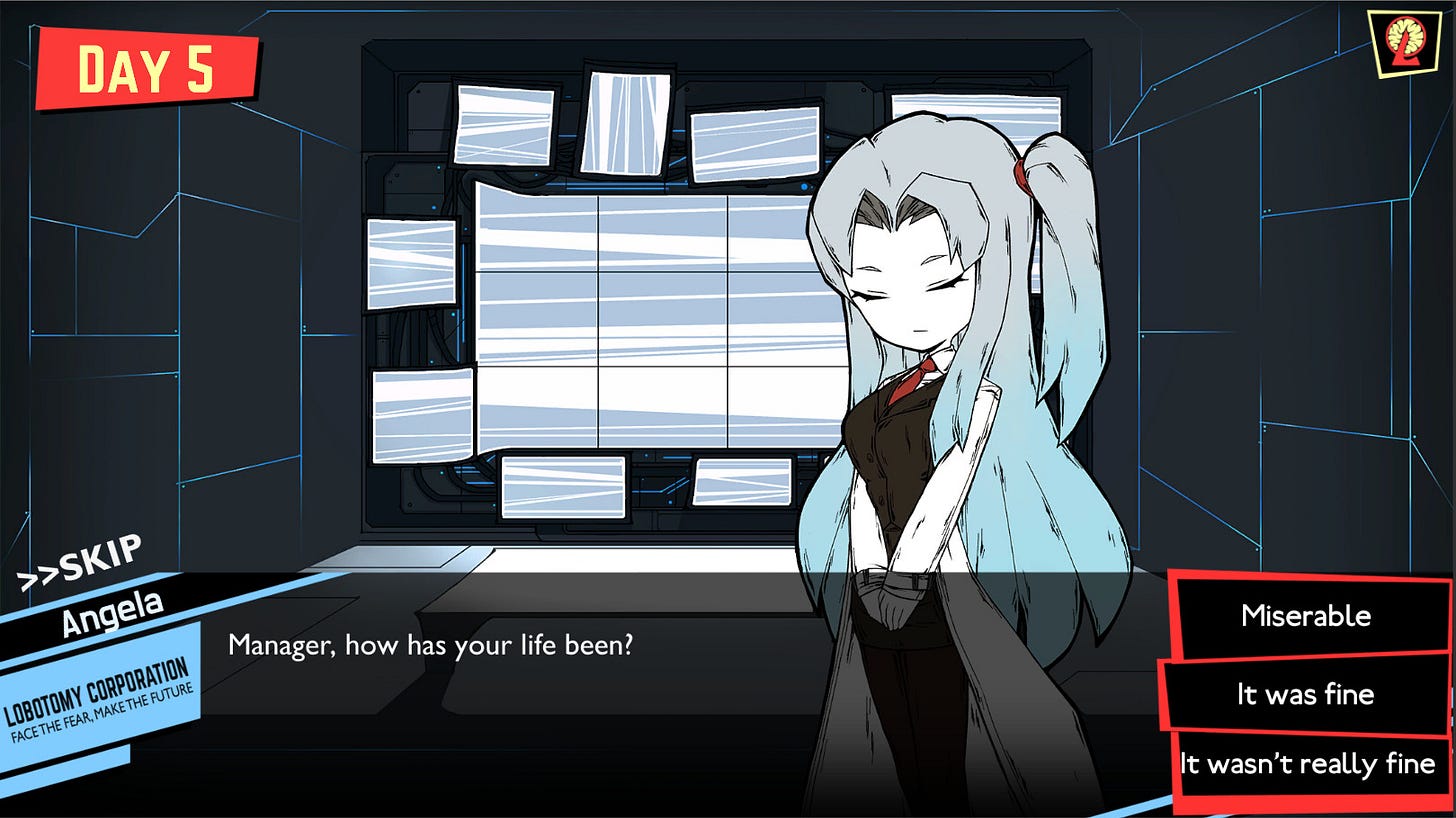

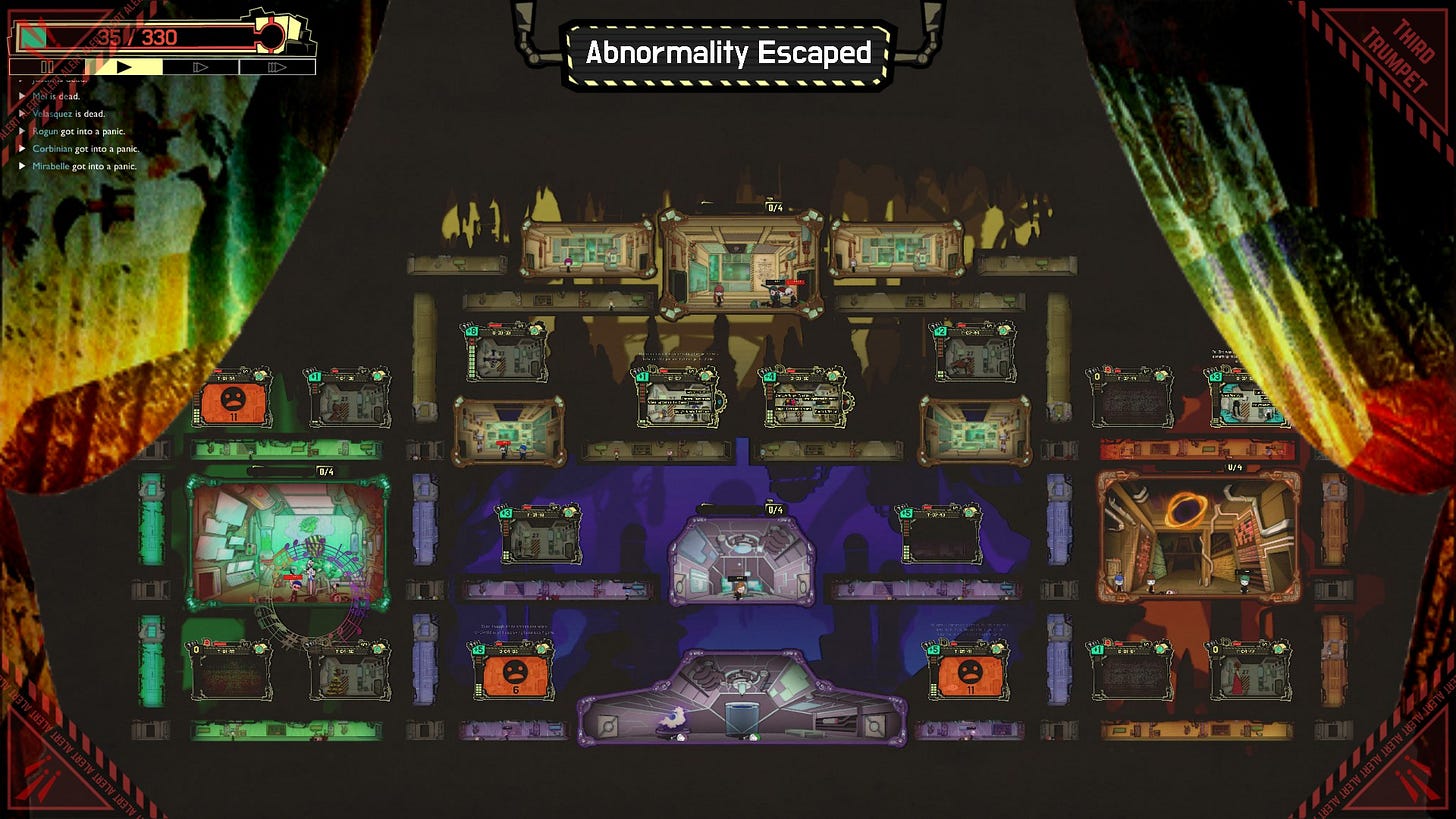

Lobotomy Corporation is a great place to start, since it’s the first of these and both requires and gives you the least amount of knowledge on the setting. Narratively, LobCorp and both of its sequels are presented similarly to visual novels: the gameplay is interspersed with written cutscenes over background art. Visually, its gameplay segments resemble something like the base management from XCOM: Enemy Unknown, but it actually plays kind of more like, say, The Sims.

Lobotomy Corporation borrows some of its premise from the tradition of things like The Lost Room, Warehouse 13, Control, or—the one of these you’re most likely to have heard of—the SCP Foundation. That is to say you’re primarily concerned with quarantining, studying, and attempting to prevent the inevitable horrifying escape of objects and creatures with unusual and often extremely dangerous supernatural properties.

The game is structured around individual days, where your goal is to meet an energy quota, collected as a result of interacting with and studying contained “abnormalities”—the in-world name for the “SCPs” here. Four out of every five days adds a new abnormality to your facility—which is also being expanded over time—and so the challenge rapidly becomes juggling every abnormality’s preferences for containment and interaction to meet your quota without any of them causing problems or attempting to escape and murder your employees. Remembering the specific favorite food and bedtime story of only four flavors of ancient unknowable evils is tricky, when that number approaches 30 and beyond things get rather hairy.

Project Moon games are notoriously brutal and Lobotomy Corporation definitely establishes that pattern. The game expects you to be okay with harsh punishment as part of the process of learning to handle each abnormality (or to be okay with looking them up ahead of time on the fan wiki). It also expects you to be returning to earlier points in the game and has roguelite-style3 persistent progression elements to encourage this. You can restart individual days, return to Memory Repository checkpoints (which save your progress every 5 days), or start fresh from the beginning, and in the latter two cases you keep all gathered research and equipment that you might have accumulated after the point it was saved. This is all also plot-relevant.

Being that this is written for ACX I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that Lobotomy Corporation and Library of Ruina, partly in the SCP tradition, have several, up-front, superficial references to Kabbalah4; your facility’s departments are unambiguously arranged in and overseen by characters named for the corresponding Sephirot (though in Lobotomy Corporation the Tree of Life is inverted), and abnormalities are given one of five threat levels named for letters of the Hebrew alphabet.

Library of Ruina is a direct sequel to Lobotomy Corporation but is a very different type of game. It’s a card battler—the combat is sort of comparable to something like Slay the Spire, but there’s a lot less roguelite here. It has deck management that more resembles TCGs, with “books” won from battle being both your card packs and how you move the plot forward.

Library of Ruina has a ton of mechanical complexity in terms of deck building and inventory management. The combat is more problem solve-y than you might expect; you have the relative advantage of seeing all your opponent’s moves and have some ability to redirect them, but, as with its predecessor, the game does get rather difficult in spurts (“the difficulty spike is vertical” is a common community meme here). While it starts relatively simple, there’s also some initial friction related to Project Moon’s reputation for having really inadequate tutorialization5. The game has manuals that explain many of the basics, even visually, but there are important things that are left very unclear.

For example, “light” is the resource that you spend on ability cards (in the screenshot above, the light cost is the number on the cards and available light are the dots above each character), but at first it seems to randomly reset to maximum and the game doesn’t clearly explain why. What’s actually happening is that you normally only recover 1 light per turn but it also resets to full and your maximum light increases whenever you increase a character’s emotion level (individual emotion levels are the number adjacent to the portraits in the bottom corners)—which can happen quickly when emotion levels are low. The in-game manual only explains in vague terms what causes emotion levels to increase and not much about what they do and why it’s a good thing. Maximum emotion level is also capped low and gated by story progression and so can’t be fully relied on to generate light in long fights (and so you need to be designing your deck to account for this). Throw multiple speed dice, page draw economy, passive attributions, and abnormality pages into the mix and deck planning becomes very complex despite only needing to pick out 9 cards.

There’s also some confusing, unexplained esoteric terminology6; your library has “floors” which is true in a literal narrative sense but in a gameplay sense this is shorthand for different teams of librarians, which are your player characters. Early battles are trying to be easy and so allow you to have multiple floors available to use per “reception”—encounters which can be one or more “acts” (battles) whose individual combat rounds are “scenes”—but they’re also so easy you won’t really need to, so it may not be clear that you’re partly intended to have multiple teams set up or have fallback teams prepared if your first is defeated. “Pages” are…well it depends on context. Normally pages are your individual skill cards (again, “books” here are essentially card packs), but key pages can be thought of as character classes—they decide individual librarians’ base stats, damage resistances, and what types of pages they can use, and contain build-defining passive abilities that can also be transferred to other key pages.

Lobotomy Corporation has a little bit of first-time-game-design jank but Library of Ruina is really where Project Moon has hit their stride. However, while I’m going to strongly recommend all three Project Moon games, for Lobotomy Corporation and Library of Ruina I’m also going to recommend that you not be afraid to use mods to cut down on some of the more annoying aspects of the difficulty7. I will definitely suggest that you try them without to see if that’s something you enjoy8, but you’ll get to a point in Library of Ruina where repeating 30+ minute battles for 2 chances at getting a card you need does sort of start to lose its charm. You can also find guides on building decks9 if that’s not something you enjoy or are good at, and again don’t be afraid to because the game is still plenty challenging even if you’re going into it with well-built teams and without grindy resource constraints.

And I mention that partly because the story of Library of Ruina is really fun and worth sticking out for because you get to see more of the City compared to Lobotomy Corporation. There’s a clever series of narrative conceits such that you start by encountering common Backstreets thugs and then progressively work your way up through all manner of the City’s progressively-more-powerful factions. It’s only slightly less ambiguous this time around whether you’re playing as the bad guys, and the game takes time to continue to grapple with LobCorp’s theming around doing horrifying things in the course of noble goals. Without revealing too much, the library keeps accidentally stealing everyone’s secrets and there’s a parade of elevating threats trying to recover them.

Taking down basic thugs eventually gets the attention of a mix of stronger gangs climbing up the organized crime hierarchy and similarly for the local Fixers. Fixers in this setting can be thought of as generic adventurers in the sense of a traditional tabletop RPG setting—independent quest takers/errand fodder. Fixers have all manner of organization, specialty, moral alignment, and explicit power competency levels, from the lowest at Grade 9 up to Grade 1 with the tip top shounen anime heroes & villains being the Color Fixers. You also eventually bump up against a couple of the Wings as things escalate10.

Getting at least part way into Library of Ruina before picking up Limbus Company is a good idea both because it gives you a good amount of additional world context and some transferrable mechanical background, despite Limbus Company being neither a direct sequel nor strictly identical type of game.

Limbus Company is a modern gacha game, which, like roguelites, could be the subject of an entire separate post in terms of describing the genre conventions and variations. If you’ve played just about any mobile game you have most of the context you’ll need to understand what I’m describing, else if you’ve played a TCG like Magic: The Gathering it’s a similar sort of business model, else imagine any other traditional style of video game and then add monetized gambling on top of it. I, too, am frankly confused why these are popular (or insanely lucrative), but Limbus Company is at least getting me part way there to understanding some of it—here it’s packaged along with a pretty interesting integrated story and set of characters, and the City is still an interesting narrative playground. All-said, Limbus Company is widely considered to be one of the most fair-to-free-only-players gachas that exists currently11.

Limbus Company is almost an auto-battler12—and you can kind of play it like one since the game gives you a big “pick stuff for me” button (that can be critically suboptimal to use exclusively)—but it’s actually borrowing a lot of mechanics, at least spiritually, from Library of Ruina. You sort of have speed die and skill decks and there’s clashing and redirecting which are still important, but now instead of dice rolls it’s coin flips and coin power, there’s damage types and mass attacks but there’s also sin affinities and resonance. I’m throwing all these out there without explanation to once again highlight that Limbus Company’s native tutorial explains all of these quite poorly—it’s bad enough that many long-time players will point you to YouTube for a better and betterer tutorial than the game gives you at the start.

The visual presentation is mixed. The UI in combat oversaturates you with useful and quasi-useful information, though fortunately the game gives you options to tone it down. The combat animations are very flashy and cool but can also make it very difficult to tell on the fly what’s going on, especially when you’re new and learning. The art, as tends to be common for anime-styled gachas, is pretty high quality—a mix of Project Moon’s traditional style with hints of Darkest Dungeon.

Limbus Company continues the trend of opening up the City to us more than its predecessors; where Library of Ruina was sort of constrained to a central location, Limbus Company very quickly shows us a large variety of locations all around the City. This time we also have a strong central cast of diverse characters whose backgrounds touch on many important factions and locations we’ve only had glimpses of so far. Project Moon still loves their superficial references; all of the player character “Sinners” are named after prominent literature main characters with varying subtlety13. The gacha pulls in this case are for “Identities”, which are mirror world alternate-universe versions of the main cast where the characters were involved with various different City factions, with different abilities and affinities.

The writing isn’t dazzling, but the scenario design is pretty good and having a large cast with clashing personalities makes for plenty of entertaining banter.

I have strong opinions on writing in video games. Mostly, it’s pretty bad. I think some of this comes down to the relative newness of games as a storytelling medium and partly on games as an art form also having quality requirements for gameplay14. Games can have good stories without having good gameplay but in my opinion15 you cannot have a good game without good gameplay. However, I’m also willing to be very permissive on what we consider gameplay. For example, I would disagree that visual novels and walking simulators16 are automatically disqualified from being good games—briefly, choose-your-own-adventure stories are a serviceable narrative vehicle and museum-like experiences are fine as long as, in both these cases, that is your operating expectation going into them.

Film is the next best comparison to video games for discussion on merits of the medium, firstly by highlighting that many crafts make up the whole—films and games will have writing and visual & audio arts that all need some element of harmony, on top of all manner of production and technical design. A film featuring a single person reading to you from a book might be widely considered to be a poor movie for not using the actual elements of the medium, in the same way we can criticize a game whose narrative is contained mostly in non-interactive elements. Secondly, we can note a clear delineation in types of film that will appeal to audiences with strongly different goals in enjoying them. A film snob will be looking for very different things in movies than someone who takes their family out Friday night to see the latest Product. There’s going to be an incredible variety in intrinsic motivation for playing video games, though video game snobbery is, uh, well, let’s just say there’s not a lot of consistent agreement.

A lot of games don’t really seem to understand how to use the medium to tell stories and I have what may be a somewhat counterintuitive example of this, Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots. Despite being a game from a series and director that is otherwise generally considered to be quite laudable for interweaving story and gameplay, the game is almost uniformly reducible to cutscenes. When it first came out someone made a 10-hour supercut of all the cutscenes, several of the CODEC calls, and a little bit of the gameplay—mostly boss fights for context—and it was frankly a pretty complete experience17. Some of this is Kojima being an eccentric auteur with a transparent primary love of film18, but also probably most modern JRPGs—and frankly most modern Japanese games in general—have this problem, despite this criticism often being aimed at western devs. A lot of games suffer from stories being told at you in way that isn’t enhanced by making them interactable.

One of my general suggestions for working around writing being difficult in games is to prefer lore instead of story. To be somewhat reductionist, lore is information about a setting with discrete context versus story being information about a setting with continuous context. If you think of it like on a timeline, a story is a continuous (or pieces of continuous) narrative along that timeline whereas lore (or any of its synonyms, such as, say, environmental storytelling) are disjointed points in the timeline of that world. Story is a video file playing from start to finish, lore is individual frames from that video.

As a critic of game design, I’d suggest that one should prefer lore to story because it allows you to do two important things. First, having this preference enshrined in your design strategy will help direct you to produce a refined gameplay experience without having to sacrifice worldbuilding. The archetypical example here is FromSoft a la Dark Souls—which is well-known both for having strong gameplay and for having a lot of its background information squirreled away in item descriptions—and this also applies for my second point, but I have a different good example.

Second, having a looser, lore-focused narrative is incredible for player engagement outside of the game. My flagship example here is Five Nights at Freddy's. FNAF and its sequels arguably have palpably bad gameplay, and, while they are top shelf horror react content, nothing else explains the series’ roiling, lasting popularity and outrageous success better than how continuously compelling it is as a piecemeal lore mystery. Ambiguity in storytelling can be a compelling tool in every medium, but works exceptionally well in media that attracts fan communities—works exceptionally well in video games.

Another underdiscussed aspect of video games as a narrative delivery vehicle is that some number of players will just never be intrinsically motivated to engage with a game’s story—some players just want to play the game. Since lore requires active engagement but tends to be optional, this means players who are interested in spending time immersed in exploring a game’s world through its lore can get a lot out of stretching their imagination, and players who are only interested in playing the game can move on and not be especially worse off for it.

The Project Moon games are a somewhat rare example of having a lore-focused world while also telling an interesting conventional narrative, and so we shouldn’t be surprised that they have a strong, dedicated fanbase. Way back at the start I compared the City to tabletop RPG settings like the Forgotten Realms from Dungeons & Dragons, Golarion from Pathfinder, or the sci-fantasy future world of Shadowrun. Lore-focused worlds and worldbuilding allow the observer to feel like a part of the world by requiring their interpretation, allowing and encouraging them to use their own life experiences to add context. Settings like these tend to have a liminality that sparks the imagination in a particular way that invites you to imagine yourself as part of that world19.

I would almost admit that quarantining the games’ narrative beats to visual novel-style segments is in violation of my general criticism that game narrative and gameplay should strive to be more closely tied together, but I think the Project Moon games are also a good example of one of the ways you can marry gameplay and theming well along other axes. The games being difficult and disorienting matches what it has to say about the brutality of its world and, by extension, the ways it’s commenting on life outside the games. Yes there’s cool anime power tiering, but also life is brutal and unfair, you have to make compromises with powers beyond your control that don’t have your interests at heart, and chances are you’re gonna have to fight for some essential thing even if the fight is ugly—often even hope is paid for in blood.

My other pet example of this style of ludonarrative harmony20 in video games is the Pathologic series21; games where the gameplay being incidentally frustrating and kind of miserable is definitely part of the intended emotional experience in ways that resonate with the narrative being delivered. Making games difficult as a companion statement to a game’s themes is a fine line that is often not executed on well; miserable games need to have satisfying payoffs lest they risk being only miserable.

Another recent-ish example of using gameplay to tell a story: INDIKA. INDIKA does kind of an unusual thing by being a pretty conventional almost-a-walking-simulator narrative-centric game, but it occasionally breaks things up to be an archetypical beep boop retropixel video game for a little bit. At first it seems kind of arbitrary but eventually it becomes more clear that the game is trying to say some subtle things about how faith is kind of like score-keeping in a video game, in that it could either not matter or be the only thing that matters, depending. The way in which the walking-simulator-versus-oh-yeah-we’re-a-game segments are so discrete is kind of clumsy, but I extremely appreciate that the game was trying not to be ashamed of being a game and it elevates what otherwise might have been a more generic experience.

One last example of the unusual ways video games can be used as storytelling vehicles both in their design and in the playing: the story of MyHouse.WAD, which I won’t default recommend you play but I suggest experiencing through how its story is told by Power Pak. MyHouse.WAD is a cryptic modded Doom map (yes, as in the old school 90s shooter Doom) that carries forth a number of modern inspirations and whose full narrative is very much in the style of an ARG. Its construction is also technically impressive with regards to how it used the available mod tools; if you’re interested in the details I suggest checking out the series of videos by DavidXNewton that starts here.

Finally, in case this is the only thing you read on video games I’d like to make the case that they’re worth your time as entertainment. Basically, I can guarantee they’re less disappointing than prestige television, though admittedly they have steeper admission fees.

First, let’s acknowledge that there’s a lot of highbrow disdain for video games, and there’s simple explanations for why. Video games are a superstimulus for accomplishment. People love MMOs because they let you live out the fantasy that your work is consistently rewarded. I love games but I think it’s a fair criticism to say they’re capable of draining motivation that might be better spent elsewhere.

Video games grab at intrinsic motivation in a way that’s unique relative to other media, and this is definitely a double-edged sword. Like most cultural products, they can bring out strong passions and poor behaviors—one need only peek in on any random Steam forum to see some of the worst of online society.

But there are a few key reasons it can be worth your while, especially inasmuch as any form of entertainment can be worth your while. If you can find the right people, you can make strong, lifelong friends over games. One of the three weddings I’ve attended was for a friend I’ve known over a decade from online games. Personally, the only direct contact I’ve had with the people from the rationalist community has been over games.

To me, there’s something slightly more elevated about a medium that requires your active participation. Similar to how I describe interpreting lore, the act of playing a game requires at least some small element of unique, individual expression. The things I love most about games are in the variety of unusual experiences they can provide and that there’s usually some element of problem-solving involved, and that’s a set of mental muscles that can be worthwhile to exercise.

Video games have an incredible genre diversity and there truly is something for everyone22. If you love competition and self-improvement, there’s every flavor of outlet for that. If you love stories there’s every flavor of that too, regardless of how much whining I do about the writing quality, and if you love love stories there’s multiple outrageously successful otome games and gachas. There’s an incredible diversity in types of puzzle games. There’s games to flatter whatever your political sensibilities are, and ones that do a good job of mocking all of them. Stuff you can play with friends.

There’s only so far I can go making specific recommendations anonymously, so let’s bring things full circle by reiterating my recommendation for Project Moon’s games. I don’t think they are complete experiences that you can truly have without playing them, but that might be either the video game snob in me talking or that the games have successfully captured my imagination. I can also recommend both that you be okay with watching story summaries and/or consider using mods to reduce the difficulty of the two of them that you can, though I also strongly recommend that you try both games as the base experiences first too—I think these games have good gameplay even inasmuch as it may be worth subverting some elements of them to experience. I think a lot of care and attention have been put into these games both as games and as a setting, and it shows if you’re willing to engage with them. They’re challenging but not insurmountable, with strong narratives and an interesting world23. Each one has their own flavor of gameplay but if you’re only there for the City there’s plenty to stretch your imagination on too, and so they’re very much worth exploring in whichever way matches your tolerances.

Lastly, as always, keep your eyes buttered till the end.

Some fan theories like to speculate that it takes place at a specific location on the moon based on circumstantial evidence regarding the official map (hence also “Project Moon”) but the apparent scale technically doesn’t fit. Though also, official sources say the population is 7 billion, which is a similarly impossible level of population density—roughly 10 times that of the notoriously cramped Kowloon Walled City.

Some districts have substantial forests and regions that could be considered rural, so it’s not strictly dense, uninterrupted buildings. Districts 19 through 21 and part of 22 also border the Great Lake. Everything else outside the districts is the Outskirts.

I’m going to be dodging an additional long paragraph trying to describe roguelites in detail by trying to summarize it as “challenging, repeated short-form gameplay with persistent external progression elements”. The archetypical roguelite examples include games like Hades or Slay the Spire.

Not to be confused with roguelike, which are games much more directly descended from, and should-be-expected-to-be-very-similar-to, the old classic, Rogue.

I genuinely promise I forgot this detail when I first decided to write this.

“Tutorialization” here is a fancy word like “onboarding”—how the game teaches you how to play the game. Lobotomy Corporation suffers from this just a little bit as well, but it’s a relatively straightforward game and does a pretty good job of introducing new mechanics gradually; Limbus Company suffers from this a lot.

This is relatively common in non-Western games and honestly this is a large part of their charm. Frankly I wish more Western games would be brave enough to be deliberately confusing and disorienting.

Library of Ruina has official Steam workshop mod support, and I specifically recommend NoGrind (makes Book and Page drops effectively infinite), BaseMod (required for NoGrind), and Achievement Unblocker (if you’d like to use these without disabling Steam achievements). There’s a variety of external mods for Lobotomy Corporation too, but I never used any—I ended up stopping short of reaching the true ending and watched a plot summary video, which is something that I think is also a valid option and might recommend for either game as well.

They both also have several mods that add content, and Library of Ruina even has a built-in reception editor.

Many of the most positive Steam reviews for Library of Ruina have something on the magnitude of 200+ hours with the game, my best estimate with using a mod like NoGrind from start to finish is something like 80+ hours. There’s plenty of game here.

I recommend the series of guides that starts with this guide by Dice_24K.

As I understand it, another common criticism with gachas is that they can be difficult to jump into later in a game’s life and supposedly this is true of Limbus Company as well, but personally I got lucky enough with early pulls (caveat: it’s common for these kinds of games to deliberately give you good luck at the start to encourage you to keep playing) that I have a very solid team capable of mostly coasting through the story. The only drawback is that there’s a lot of intended team diversity I’m missing out on without spending big bucks on pulls but again I haven’t hit a wall that wasn’t overcome just by straight leveling up. There have been a few extremely difficult bosses but there’s only maybe one so far where a specific character I had made a difference versus just playing mechanically better.

The wikipedia article for "auto battler" links the genre name to descendants of Dota Auto Chess, which, as I understand it, isn’t strictly accurate—there have been multiple subtypes of this in mobile games long before Dota Auto Chess and, at the very least, this kind of thing was a custom game staple in ancient RTS games like Starcraft and Warcraft 3. Auto-chess-style games are usually just called auto chess and are better thought of as a subgenre of auto battlers. Auto battlers are usually centered on some form of setting up teams and then mashing them up against enemy teams in a way that is played out without significant player input once the action has started. This has been fertile ground for gachas for a long time, since you can tie the monetization to building complex teams and then also unfairly scale the enemy encounters to encourage people to spend time or money making their teams more powerful. This is the kind of paragraph I was trying to avoid for describing roguelites and gachas.

Their character arcs and personalities also tend to mirror their source inspirations in some manner. Here’s the full list for a bit of fun trivia, in numerical Sinner order (h/t this new player FAQ by solaariel):

Yi Sang — the author and presumed first-person main character of the Korean novel, The Wings

Faust — of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s play on the classic German legendary character

Don Quixote — The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes

Ryoshu — based on the subject of a Japanese short story by Akutagawa Ryunosuke called the Hell Screen

Meursault — the main character of a French novella The Stranger by Albert Camus

Hong Lu — Hong Lu’s given name seems to be a reference to the title of the relatively obscure Chinese novel Xiùxiàng Hóng Lóu Mèng (Dream of the Red Chamber) by Cao Xueqin, but his proper name, Jia Baoyu, is also shared with its main protagonist

Heathcliff — of Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte

Ishmael — from the American classic Moby-Dick by Herman Melville

Rodion — from Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment

Dante — of the Divine Comedy

Sinclair — from a bildungsroman by Herman Hesse titled Demian: The Story of a Boyhood

Outis — a reference to the pseudonym used by Odysseus when confronting the Cyclops

Gregor — from The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka

I’m going to sort of dodge around defining gameplay because I think that gets way too into the weeds for no payoff. And also partly because come on it’s in the word there, it’s like “mouthfeel”, it’s not that you need an explanation, it’s a fuzzy concept that’s sort of intuitive once you engage with it. We’re talking about what it feels like to play a game. It’s gotta be good, pending the few exceptions where misery is an intended part of the experience.

This will be the last time I use this phrase, subjectivity is implied.

“Walking simulators” are a quasi-recent, mostly-western style of game that often include minimal gameplay elements aside from moving around an environment where often the story is told at you. The quintessential example of this is Dear Esther.

You could make a counterargument here that the supercut including gameplay at all is undermining my point, and/or you could go on to make a further argument that this also applies to watching a Let’s Play—that most games can be experienced by watching (others play) them. My admittedly weak rebuttal to this is that you won’t have fully experienced them by doing this, but I’m sympathetic. As a video games enthusiast, I would strongly recommend playing games as the primary way you spend time with the medium, but I love them strongly enough that I wouldn’t criticize you too harshly if your preference is for watching others play them.

This extremely understates Kojima’s influence on video games though—his games are constantly calling shots on things that go on to become popular staples in games or are eerily accurate cultural predictions. Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater is one of the first games to have rudimentary survival mechanics. P.T.—a teaser for a game that was never actually made—singlehandedly revolutionized horror games. The last parts of Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty was an absurdly prescient series of predictions on the internet in general from 2001. Death Stranding’s commentary on social atomization seems quaint in a post-COVID world until you remember it started development in early 2016 and released November 2019.

That said, it’s an important part of worldbuilding that there be concrete answers, even if they’re not clearly revealed—fans will very quickly notice when you’re making it up as you go along.

The obscure good-twin to the much-more-common “ludonarrative dissonance”, when the narrative is subverted by the gameplay. For example, when your main character brutally murders hundreds of henchmen in the gameplay and then abhors any and all violence in the cutscene.

The HD remaster of the original and it’s remake/sequel. Part 3 will have been out recently as well.

Finding the right hardware can be tricky, and will probably be what most constrains your options. There’s a ton of mobile games you can play on your phone but they’re usually not near the apex of general quality. Consoles and desktop computers aren’t strictly cheap but if you already have the latter you will instantly also have a ton of options spanning the entire history of gaming. You don’t really need “gaming” hardware unless you’re only interested in modern titles.

Also, this didn’t fit anywhere else but they all have pretty banger soundtracks.